By Margarita Lysenkova, Manager – Sector Program, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

Ores mined in war zones have long been subject to heightened attention when it comes to sustainability and reputational risks. Yet in 2022, it is the production and sourcing of ‘soft’ commodities, like wheat, that are increasingly under scrutiny.

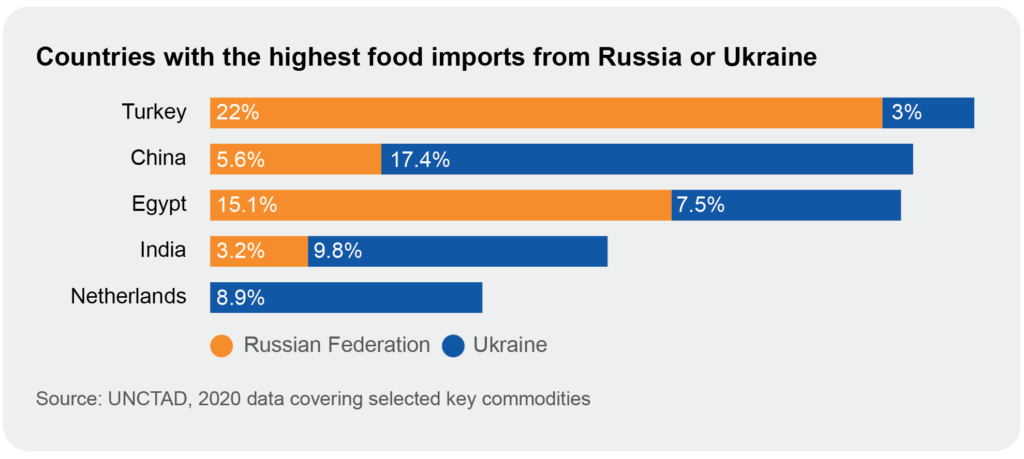

As the conflict in Ukraine continues to escalate, the impacts on sustainable development become more pronounced, and the vulnerabilities in global food supply chains are increasing. Almost half of the world’s calorie intake is derived from essential crops, such as maize, rice, and wheat – and according to World Bank analysis, Ukraine and Russia account for 29% of global wheat exports and 17.4% of world trade in maize. Supply of crucial cooking oils and fertilizers has also been affected.

Many companies have suspended trade and operations in Russia due to sanctions and stakeholder pressure. While the diplomatic agreement reached to unblock Black Sea trade routes from Ukrainian ports offers some encouragement, uncertainties remain. In addition, concerns over products being obtained under extortion add to the challenges for companies involved in commodity trade throughout the region.

Rights to food are being eroded

It goes without saying that when agricultural areas are devastated and water installations destroyed, the right to food of the local population is violated. Yet the impact of the Ukraine crisis spreads well beyond the nation’s borders. It is expected that many millions will be at risk of hunger globally as a result of tightening supply and affordability of essential crops, which comes on top of existing difficulties that have already been exacerbated by two and a half years of COVID-19.

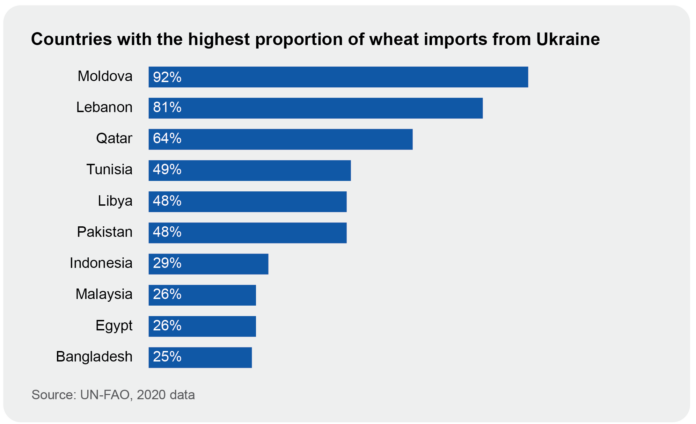

Not all world regions are exposed in the same way. Where people are already experiencing severe poverty, the risks of hunger and malnutrition are much higher. As the World Food Programme has warned, countries dependent on food exports from the conflict-affected region are being hit hardest. Meanwhile, to prevent local shortages, we are seeing some countries restricting food exports, which may further impact the global supply.

When viewed from the human rights perspective, the right to food for many is not primarily about a lack of sufficient quantity but lack of access – largely due to affordability. However, with continuing declines in Russia-Ukraine food exports, we are seeing heightened concern over insufficiency of food availability. Less crops harvested and planted in 2022 is likely to instigate a spiral of worsened food security in the year ahead.

Global baseline for transparency

Most food is produced, processed, traded, and distributed by private businesses. At the same time, when an individual company looks at their impacts on food security in isolation, it often struggles to determine them. Multinational companies may also focus on developed markets where food security is not a significant concern. The risk is that food security is perceived as a macro “development” issue, which is why expectations for transparency on food security is relatively new for many companies.

The GRI Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fishing Standard (GRI 13), launched in June, supports any organizations operating in these sectors to communicate and disclose their sustainability impacts in a comprehensive and comparable way. This new reporting standard singles out food security as one of the significant issues that companies need to consider, providing a new global baseline for transparency on the topic.

As GRI 13 recognizes, there is no silver bullet solution to global food security. A myriad of approaches and actions are needed, including:

- Strengthening capacity for farmers to increase production and supply, such as a newly launched US$1.5 billion African Emergency Food Production Facility that is delivering urgently needed seeds and fertilizers and helps producers to cover food shortages in the region. Rising fuel and transportation costs is another pressure on farmers’ incomes, further increasing the vulnerability of small producers. By reporting their contribution to economic inclusion of farmers, companies can demonstrate the role they are playing – and where more action is needed.

- Partnerships and collaboration to alleviate food security concerns, with some companies working with governments and international development institutions. For example, a link up between the International Finance Corporation and Olam Agri will boost exports of wheat, maize and soy to developing countries. The existing distribution channels of companies can be leveraged in cases of a crisis for a prompt response. This why GRI 13 recognizes partnerships on food security as key information to report.

- Greater action on food loss, to ensure more food is persevered for human consumption. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, globally 13.8% of food is lost from harvest to retail. And of course, mitigating food loss also brings cost savings and economic benefits, while reporting can help assess the efforts to minimize food loss.

- Food sovereignty policies, which emphasize local resilience within agriculture systems, to help countries that are largely dependent on food imports to redress the balance and reduce vulnerability to crises in other regions. Localized food production also reduces the distance between producers and consumers. By reporting actions to strengthen food security at the local and regional level, companies can highlight how they address food security locally or regionally.

- Trade-offs and compromises – such as those related to land use for products, or changes to align dietary choices with sustainably produced food. As the EAT-Lancet Commission report outlines, food production needs to shift to be beneficial for both human health and the environment. This means businesses need to be taking active decisions about how they are using land and natural resources.

A persistent and pressing challenge

The actions of the companies producing the essential food and materials on which humanity’s survival depends can be a multiplying factor when it comes to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. And given we are presently on a trajectory to fail to reach SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), with 800 million people going hungry every day (according to a UN Food & Agriculture Organization report), it’s clear that we need private companies to take greater accountability for their food security related impacts.

The global population is projected to rise to 10 billion by 2050, meaning that we can expect the issue of food security will continue to rise up priority lists – for governments, policy makers and big business alike. That means that civil society groups, responsible investors and other stakeholders will press companies to be transparent.

Food is more than just a commodity that can be left to the whims of market forces – nor should its supply and security be undermined as a consequence of armed conflicts and natural disasters. The integration of food security considerations into the sustainability strategies of companies, as encouraged through GRI’s new Sector Standard, is a crucial next step towards the long-term solution.

Margarita Lysenkova joined GRI in 2019 and has been instrumental in the development of the new Sector Program, where she has led the pilot project for the development of GRI 13. With a professional background in corporate, UN and non-for-profit sectors across four countries, Margarita’s expertise spans international labor standards and sustainability. She has previously worked for the International Labour Organization in Geneva, and in a financial reporting role with a Belgian multinational. Margarita holds degrees in economics (Saint Petersburg University of Economics & Finance) and business management (ESC Rennes School of Business).

Margarita Lysenkova joined GRI in 2019 and has been instrumental in the development of the new Sector Program, where she has led the pilot project for the development of GRI 13. With a professional background in corporate, UN and non-for-profit sectors across four countries, Margarita’s expertise spans international labor standards and sustainability. She has previously worked for the International Labour Organization in Geneva, and in a financial reporting role with a Belgian multinational. Margarita holds degrees in economics (Saint Petersburg University of Economics & Finance) and business management (ESC Rennes School of Business).