Our Did You Know? series, by contributing editor Mary George, covers hot topics and innovative technologies in the rapidly evolving food and beverage processing and packaging industry.

Chances are that you have “eaten” a package or two already today, that is, if you take any pill or supplement in a capsule. Both hard and soft gel caps have been around since the mid-1800s. So, though the concept of eating a package is well established, recently, the growth of edible – or almost edible – packaging materials has been picking up speed.

Where is the surge in demand for food or beverage packages to be edible, or at least made from a food-compatible material, coming from? When we eat packaged food, we basically “eat” the packaging via contact with the materials the food touches, according to Safer Made, a company that identifies and invests in technologies and products that work well without using harmful materials. Thus, the materials in packaging need to be treated like the ingredients in food and composed from the healthiest options available.

A 2019 report commissioned by Safer Made identified three forces that influence how consumers feel about packaging and drive companies to make a change:

- Concern about plastic pollution in waterways and oceans. Almost all persistent plastic pollution is caused by petroleum-based plastics.

- Waste. Packaging is usually thrown away. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, packaging makes up about one-third of municipal solid waste. In addition, food waste can be caused by inefficient packaging.

- Exposure to potentially harmful chemicals. Think of all the BPA consumers have been exposed to over the years. While the jury is still out on the exact health effects, the FDA continues to update its regulations and research into the chemical. This, and concerns with other potentially harmful chemicals, could be remedied by packaging that is made from food-grade or safe biodegradable materials.

You can have convenience and eat it too

You’ve seen them before, but maybe not in your protein shaker bottle. Clear pouches filled with a powder or liquid are commonplace in the detergent aisle. Obviously, these pods are not edible, but a few years ago, Kuraray’s MonoSol, a leader in this technology, began work on bringing this concept into the food and beverage space.

Made with Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVOH), the food-grade film for the pods hit the market in 2018 with several partners, including Vade Nutrition and Nature’s Bounty, taking the lead and producing protein powder pods and pre-workout capsules.

“This is food-grade material and a different chemistry than pods for household products,” said Dorota Bartosik, MonoSol’s senior manager, new ventures marketing. “It is manufactured differently and specifically for use with food products.”

At first glance, the film may look like plastic, but it is a colorless and non-toxic polymer that is made from 100% food-grade ingredients. MonoSol’s GRAS – generally regarded as safe – certificate was evaluated by the FDA and received a positive response of “no questions asked.”

Designed to totally dissolve in liquid, MonoSol’s food-grade film is non-nutritive, is not absorbed by the body, and, in its dissolved state, passes straight through the body. Once the material makes its way to the wastewater stream, it is consumed by bacteria and other microorganisms and converted into water and carbon dioxide.

“This is an opportunity for the consumer who wants convenience and a clean footprint,” said Matthew Vander Laan, MonoSol’s vice president of corporate affairs. “Acceptance by the market so far is comparable to laundry pods. Consumers want the convenience factor, and our partners have seen uptick in sales as the protein pods are an added line in most cases and do not cannibalize existing sales.”

The pods have the potential to reduce plastic use, for example, if consumers who normally purchase single-serve bottled protein drinks replace those with a protein pod in a reusable bottle.

MonoSol’s film has other applications in the food and beverage space as well. It is being used in manufacturing to add hard-to-handle ingredients such as food coloring. “Because the [food coloring] powder doesn’t have to be scooped, a manufacturer is able to save money on equipment to prevent airborne particles,” Vander Laan said. “The film does a nice job in that space as production or processing aid.”

The material is also ideal for ingredients such as spices, sugar, or enzymes that need to be manually added into smaller batches. It helps speed up the process and ensure every batch is the same. The same concept applies in food service for use in food preparation.

And speaking of food service, MonoSol is developing a product that you might see in the front of the house.

“We are currently working on prototypes for ketchup packets,” Vander Laan said. “These wouldn’t be consumed, but the material is biodegradable, a fact that is important to consumers. This would give brand owners the opportunity to provide an end-of-life for the packet, as opposed to having branded litter on the streets.”

Driving change from sustainable to regenerative

In order for a product to make it in the marketplace, there must be demand. According to a recent report, the global Edible Packaging Market was priced at $727.6 million in 2018 and is expected to reach $ 1.1 billion by the end of 2025.

But dollars, while important, are not the only factor influencing packaging innovations. According to Marty Mulvihill, Safer Made co-partner, companies and the people behind them have the mindset that they are doing important work besides building a business. “They are looking for the best, environmentally friendly way to bring safer products to the market,” he added.

The motivation goes beyond safer, bio-based products. “Companies are looking at how they can reduce energy and water use, lower the manufacturing impact, and try to get to a place of less bad and more good,” Mulvihill said. “I see the mindset moving from sustainability to a regenerative approach.”

It was this line of thinking that brought Apeel Science to life. One of the founders, James Rogers, was listening to a podcast on food waste and insecurity while driving through California’s “Salad Bowl.”

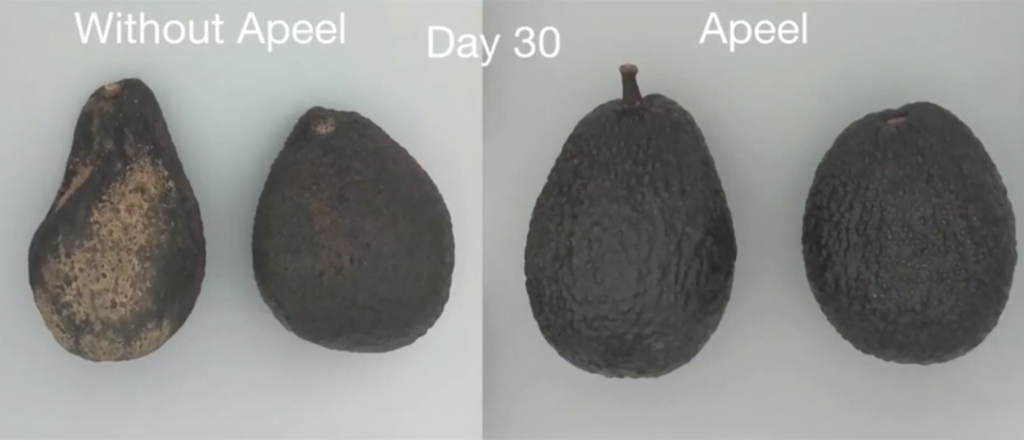

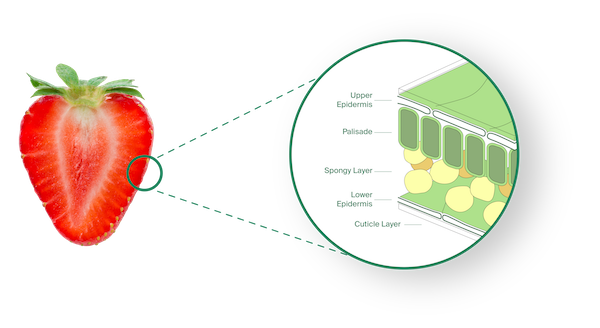

This inspiration led to the development of a product that can extend the post-harvest life of produce. Apeel, based on how fruits and vegetables maintain their own shelf life in nature, is made of plant-derived materials that exist in the peels, seeds, and pulp of all the fruits and vegetables. When applied, it forms a thin “peel” of edible plant material on the surface of the produce. This colorless, odorless, and tasteless barrier slows down water loss and oxidation — the factors that cause spoilage.

“Enough food to feed the world is produced, but it is not getting to where it needs to be,” said Jessica Vieira, Apeel’s director of sustainability. “Working from how a fruit or vegetable maintains its shelf life on its own, we refer to what we do as operating with nature. We are not creating something new.”

Apeel’s customers are retailers and produce suppliers. The coating is applied post-harvest, usually where produce is cleaned, sorted, and packed. “The product gives suppliers more time to distribute, so maybe they can ship slower to lower costs or stop using shrink wrap,” Vieira said. “Retailers can see up to a 50% reduction in food waste, along with a potential uplift in sales because customers have a better experience and the purchase is less risky. And customers don’t pay any more for produce with Apeel.”

In late 2019, Kroger announced that it would begin selling Apeel produce. “Kroger is excited to offer more customers Apeel avocados and introduce longer-lasting limes and asparagus, marking another milestone on our journey to achieving our Zero Hunger | Zero Waste vision,” said Frank Romero, Kroger’s vice president of produce. “Apeel’s innovative food-based solution has proven to extend the life of perishable produce, reducing food waste in transport, in our retail stores, and in our customers’ homes.”

The savings add up

Every piece of produce needs to be grown and requires water, land, storage, packaging, and all of the resources that go into getting produce to the store shelf. These are wasted if the fruit or vegetable spoils before it is eaten. Consequently, when food isn’t wasted, less has to be produced and resources are saved.

According to Apeel’s data, for every avocado treated with its coating, 23 liters of water are saved and 30 fewer grams of greenhouse gases are emitted. These savings account for the impacts from manufacturing, distributing, and applying the Apeel coating. “We take into account what it takes to make and apply Apeel and are excited about being able to drive the numbers [resource savings] and reduce our impact,” Vieira said.

When almost edible makes a difference

Certain packaging components, though made from plant, natural or even food grade materials, will never be edible. For example, exterior packaging that could be contaminated during shipping, handling, or on the store shelves, wouldn’t be safe to eat. But that doesn’t preclude the need to find better and safer options.

Take six-pack can rings. You would never consider eating one, no matter what it was made from. But this one packaging product has been shown to cause environmental damage and, until recently, has only been made of plastic.

Conceived from one person’s desire to “eliminate all plastic” the E6PR™ (Eco Six Pack Ring) can ring was born. After winning a Cannes Lions award in 2016, the E6PR design went viral and the team behind the concept decided to go from idea to production, according to Ricardo Mulas Ochoa, E6PR director.

The can rings are made from food by-products using silage left in the field after harvest that would have been burned or used for livestock. The natural fibers make the rings compostable. The material isn’t meant to be eaten, but if a ring makes its way to the ocean or a field, animals can eat it without suffering any ill effects. And, unlike plastic six-pack rings, which last for decades, E6PR’s naturally disintegrate.

Mechanically processed without chemicals or glue, the rings are 100% plastic-free. Testing has been done to show the E6PR rings to be as strong as plastic, as well as meet the company’s ecological claims.

E6PR was developed in conjunction with early pioneers including Saltwater Brewery in Delray, FL, and other brewers and beverage producers. The product hit the market in 2018.

“Currently, we are manufacturing on a small-scale basis by third parties,” Ochoa said. “We are building our own facility in Mexico City that is estimated to be up and running in 2021. Our aim is to reach efficiencies and economies of scale, which will allow us competitiveness from a price standpoint. And we work with our customers to help them find the right way to switch to this new solution in their production line.”

At the moment, E6PR is mainly relying on word of mouth and is finding that breweries are coming to them. “Sometimes moving slowly is the fastest route,” Ochoa said. “Our In-house R&D pipeline is working solutions for all types of cans. We will work on all of those first and then any type of packaging, we’ll try to tackle it.”

Edible or not packaging influences consumers

An internet search for “food and beverage packaging trends” brings up very similar lists and all with some form of “sustainability” near the top. This term has been around for so long that it really isn’t a trend, but what is expected. Consumers drive change, and packaging companies, both well established and start-ups, are quickly responding.

“Bio-based and edible resonates very well with consumers,” Mulvihill said. “As consumers see it, something that is edible is likely to be safer than a PET-based plastic. Consumers are moving beyond green and increasingly looking for health and wellness. This segment is growing rapidly and causing a shift in store shelves and product line-ups.”

When Safer Made launched three years ago, the group had just a handful of companies seeking funding. In 2019, Mulvihill said the number grew to 30, with the biggest increase in the packaging sector focusing on concern in ocean plastic pollution.

He added: “My observation is that companies are looking at more food-compatible materials such as starch-based or algae-based packaging, innovation of products that will be there for the long-term to compete with plastic.”